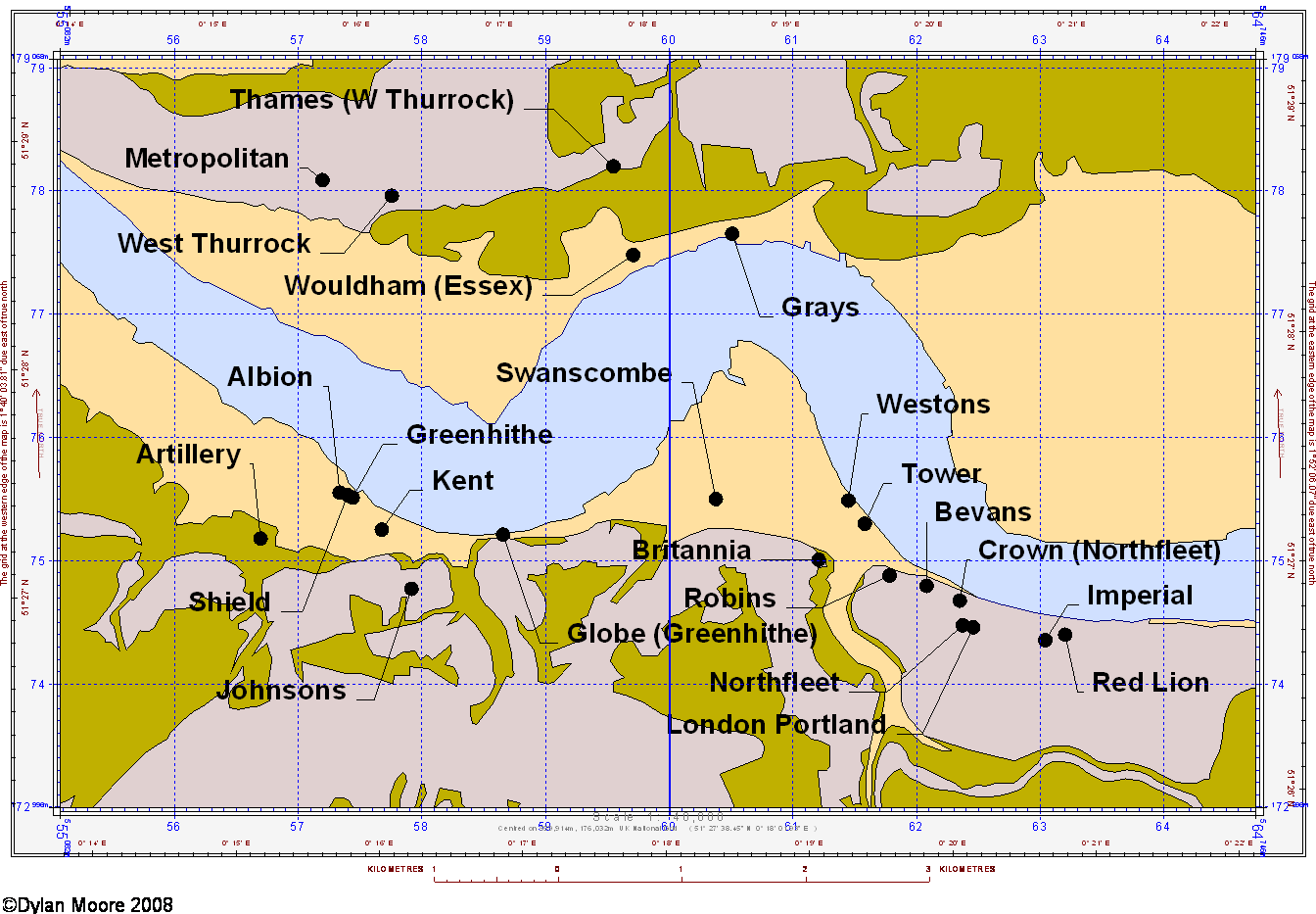

The plant names on this map are clickable unless re-sized by device.

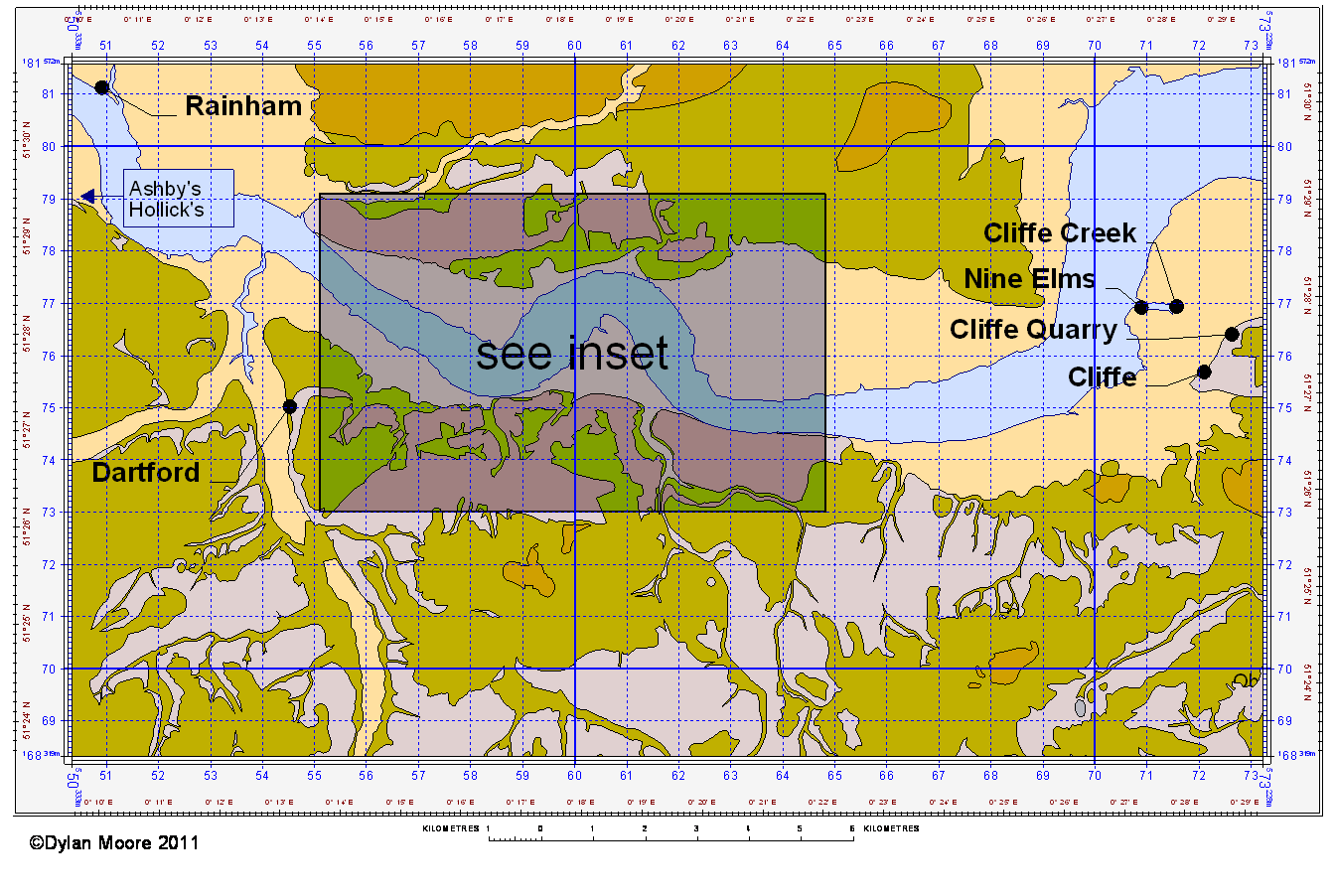

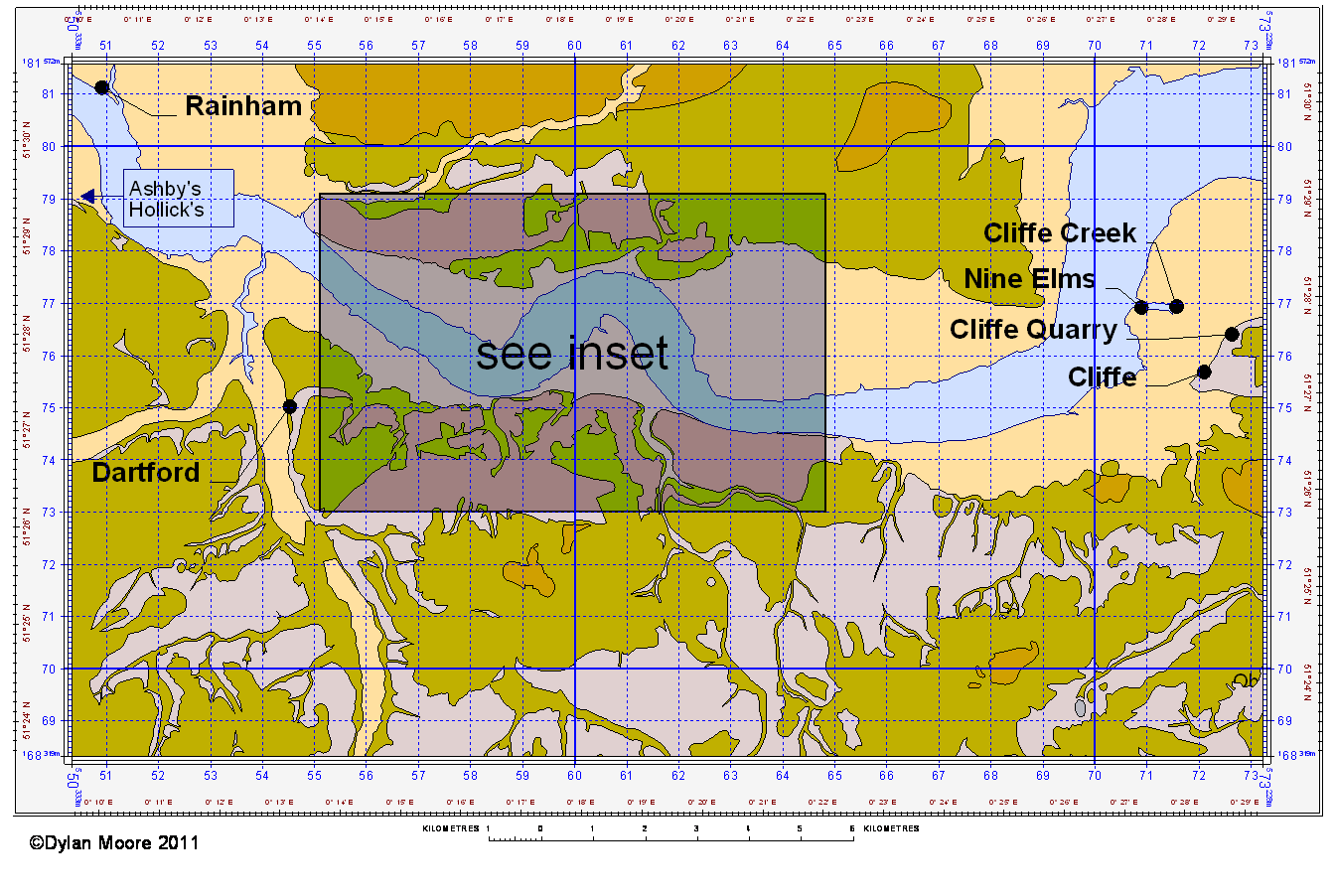

The Chalk appears in the Thames and Medway areas as an escarpment generally dipping slightly northwards. Its scarp face, a few kilometres to the south of the maps, constitutes the North Downs. Moving north towards the river, in the Thames area defined, the chalk undergoes a slight upwarp, resulting in an anticline stretching from Greenwich to Cliffe, before plunging deeply beneath the London Basin in Essex. The result of this is a short reach of the river, as shown in the inset map, in which chalk hills reach down to the river bank on both sides of the river. The area therefore emerged early – at least as early as the Roman occupation – as a source of chalk for lime burning in the London area, and more importantly as a source of ballast for returning ships that brought bulk goods to London.

See "Northfleet in the time of James Parker"

The reach between Dartford and Gravesend was therefore much quarried before the cement industry arose, and cement plants often established themselves in old quarries. The Thames-side chalk is Upper Chalk of high purity, and is mostly highly porous with water content of 30-45% by volume. It contains 5-10% flint in frequent horizontal bands, which are easily removed by wet processing. The chalk is often overlain with tertiary sands and drift deposits, which can be thick enough to make extraction of the chalk un-economic. By 2008, when Thames area cement production ceased, virtually all the readily-available chalk had been quarried out, leaving the area dominated by the cliffs of old workings.

The clay component for cement manufacture was initially alluvium from the Medway, the transportation route having been already established by the importation of septaria for Roman Cement, delivered by huge fleets of barges dedicated to the work. The Medway alluvium was siliceous but fine, and therefore an excellent component, and gained a wide reputation as the “ideal” clay component: manufacturers all round England and even as far afield as northern France used it. Alluvium from the Thames banks was soon found to be adequate. The marine chloride content of alluvium rendered it much less suitable for rotary kiln operation, and later London Clay was used, the largest deposit being that on the Essex bank, where it was generally processed on-site and pumped as a slurry to the plants, often over many kilometres.

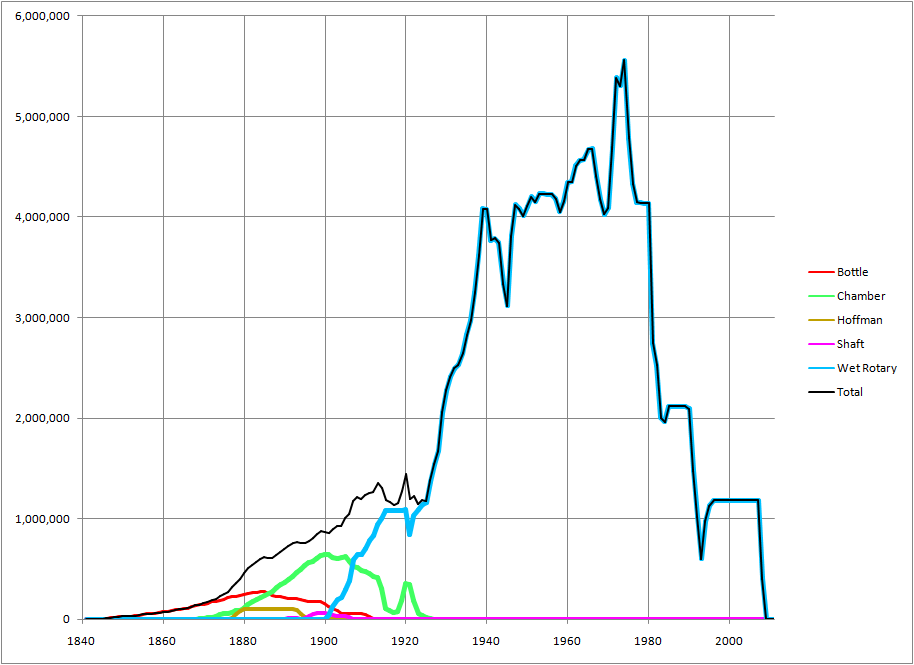

The Portland cement industry was born in the area, with William Aspdin’s short-lived Rotherhithe plant established in 1842, followed by White’s Swanscombe plant in 1845 and Aspdin’s new plant ("Robins”) in 1846. It was attracted by the London market, the excellent transportation links, and the suitability of the materials for low-technology processing. Capacity peaked at over five million tonnes in the early 1970s, but being tied to energy-inefficient wet processing, production nose-dived after that, and finally ceased altogether with the closure of Northfleet in 2008.

As one of the world’s great concentrations of the cement industry, on a par with the Lehigh Valley in the USA, the area remains profoundly affected by its industrial legacy, with a large proportion of the land area consisting of worked-out quarries, many of which are of spectacular size.

Evolution of capacity (annual clinker tonnes) in the Thames area: