As an appendix to her section on the cement industry, Lesley Cook gave extracts from A Century and a Quarter by C G. Dobson. The book, written by one of their directors, was published for private circulation by Hall and Co. Ltd. in 1951 as a celebration of the 125th anniversary of the company. It includes a description of the brief interlude in the company's activities in which it attempted to set up as a cement manufacturer. It provides an interesting example of the development of the industry in the critical decade 1900-1910, when a large number of gung-ho new entrants thought they would try their hand at what looked like (to the outsider) a good way to make lots of money without too much effort. It differs from other accounts in its honesty - a commodity hard to find in the industry of the time.

Hall & Co. were a company of coal and building material merchants that grew in concert with the improvements in transportation that occurred throughout the nineteenth century. In particular, it was intimately (but informally) associated with the Surrey Iron Railway - Britain's first public railway. The company's founder - George Valentine Hall (1786-1845) - came from Horsham, Sussex, and began as a labourer at the Merstham Greystone Lime works in the North Downs in Surrey, south of London. Merstham was one of the famous localised sources of hydraulic lime listed by Smeaton in his work, and was one of the major sources of hydraulic lime for London. The Surrey Iron Railway was built from Wandsworth on the Thames to Croydon, and opened on 26/7/1803. It was subsequently extended to Merstham. It allowed building materials (Merstham lime, but also Dorking Greensand - used as a building stone) to be brought down to the Thames for distribution throughout the capital. It also allowed sea-borne coal fuel to be moved up into the expanding South London suburbs. G. V. Hall, having taken over as operator of the Merstham plant, promptly set up as a merchant operating along the length of the railway, moving coal and coke southwards and building materials northwards. Although the horse-drawn Surrey Iron Railway became obsolete and closed in 1846, its successor, the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, offered an extended area for business, with a web of branch lines over South London and lines fanning out from there to the south coast. Hall's marketing area became identical to the area served by the railway. The firm went public as Hall & Co. Croydon, Ltd on 13/7/1898, and rapidly expanded to become Britain's biggest builders' merchant.

The formation of APCM in 1900 caused consternation among builders' merchants. It was assumed (not without reason) that the hidden agenda of the Combine was, if not to "cut out the middle man" altogether, at least to force down their profit margins. As a result, larger merchants were determined to make their own cement. Others in the London region who embarked on this were Goldsmith's (British Standard) and Broad's (Cliffe). Hall's were the first to build their own plant, as explained in the article, because they were already seriously considering it before the formation of APCM.

The following account is from pages 79-84 in Dobson's book.

The Directors’ Report presented at the 1903 Annual General Meeting mentions a further increase of £4,145 in the net profit, and contains the first public intimation of the Board's decision to build a cement works.

In the freehold land at Beddington from which gravel is being removed, a valuable bed of clay has been uncovered. Both the chalk and clay have been carefully tested and found suitable for making cement, of which the Company sells very large quantities at its various depots.

The Directors have, therefore, after careful consideration, decided to erect works for the manufacture of cement by the most approved and up-to-date methods, in the confident hope that they will prove a valuable addition to the earning power of the Company.

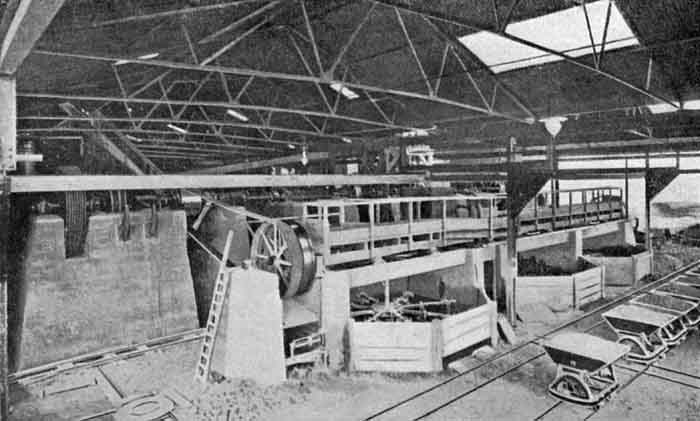

View of the plant from the east

View of the plant from the east

View of the washmills from the NE. To the left is the north end of the rope drive, from which a common drive shaft for the three mills is taken. The area behind contained pumps and probably mixers.

View of the washmills from the NE. To the left is the north end of the rope drive, from which a common drive shaft for the three mills is taken. The area behind contained pumps and probably mixers.

The decision to build a cement works was not due entirely to the discovery of that bed of clay under the Beddington gravel. The idea had been germinating in Mr Joe's mind ever since he had joined the firm, and it was probably in his father's mind long before that. It was at first intended that the works should be at Coulsdon, where we had chalk (Note 1), but not the other essential constituents of cement making—clay. This scheme had to be abandoned because in 1898, after a long correspondence, our Coulsdon landlord refused permission to build the works (Note 2). But the idea persisted.

In July 1903 Mr Harry (Note 3) went to the United States "to examine and report on the Rotary Kilns and other equipment now in use for making cement in America". Works were also visited on the Continent and in Sweden to ensure that ours should be the most efficient in England.

Even after the statement made in June, 1903, Mr Harry and Mr Joe (Note 4) were not satisfied that Beddington was the ideal site for the Works. At a Board Meeting on 29th December it was agreed that the Works should be built at Ewell (Note 5), but this decision was rescinded in January, 1904. The Board reverted to the Beddington scheme, and plans were made for building to start as quickly as possible. We cannot tell in detail of the alternating periods of hope and disappointment that attended the building of the works. Progress was far too slow for Mr Harry and Mr Joe: the latter in particular found the delays irksome, and early in 1905 went to Dessau with Mr Maxted, the Consulting Engineer, to see Mr Polysius, the designer, and offered him a bonus of £500 to complete his contract by a certain date. The Ferbeck Construction Company were also in trouble with Mr Joe about delays in the erection of the two chimneys (Note 6).

Our records do not, in the main, justify the strictures of the two Managing Directors on the men and firms concerned. Rather do they suggest that this girding at the slowness of erection was due to the impatience of Mr Joe to see the accomplishment of an idea that had been germinating in his mind for at least twenty years. His co-directors did not share his enthusiasm, and were thankful when the works were at last sold.

The date when the first cement was made at Beddington is not recorded (Note 7), but it was between July 1 and October 1, 1905. The Chief Chemist was Mr G. Edon Brown, a fearless critic when he thought the Board's policy unwise. The chief engineer was Mr Hawke.

In October 1905, a handbook entitled A New Industry in Surrey was printed by the company and widely circulated. Here are some extracts from the text:

About two miles from Croydon, in the County of Surrey, lies the picturesque little village of Beddington, like a rural island in the midst of the flowing tide of the on-coming population which spreads out from our great metropolis. Its creeper-clad cottages still nestle in sylvan seclusion by the River Wandle, whose banks are here overhung by magnificent elms, ancient yews, and willows. A pedestrian, wending his way from Beddington village along the lane, would presently see on his right, about half a mile from the lane, two tall chimneys on which are inscribed "Hall & Co., Croydon, Ltd." These are the chimneys of the new cement factory, and the making of Portland Cement is the new Surrey industry.

THE WORKS AND THE WORKMEN

The building of these works employed many hundreds of labouring men during the winter of 1904 and 1905. On starting the manufacture of cement, however, the bricklayer and his mate were superseded by the more highly trained mechanic. During the fixing and starting of the machinery it was necessary to employ German mechanics as these alone understood its proper management. It was very interesting to note in this connection the extraordinary adaptability of the English mechanic and even of the labourer, who not only learned to operate the various machines, but quickly superseded the German workman in all departments, so that now it is almost impossible to hear the German language spoken about the works. it now employs a large number of labourers, engine drivers, electricians, fitters, burners and millers; and the readiness of the British workman to change from one job to another is quite remarkable.

The comfort of the workmen has received careful consideration by the provision of a spacious mess room with a large range for cooking meals. At the back of the same building are situated the bath-room and lavatories. Modern cottages (Note 8) have been erected near the works for the accommodation of some of the men, particularly those who work at night.

The installation, which has just been completed, is unique in many respects, and for up to date design, size, and the minute attention which has been paid to every detail conducive to efficiency and economy, is unsurpassed in this country. If at any time it is found expedient to enlarge the works, this can be accomplished at comparatively small cost, as the whole has been designed with this end in view.

The works are very compact, and have been arranged in a most systematic manner, the raw material coming in at one side and leaving as the finished product at the other. During this journey the material is not touched by hand until it is deposited as finished cement in the store.

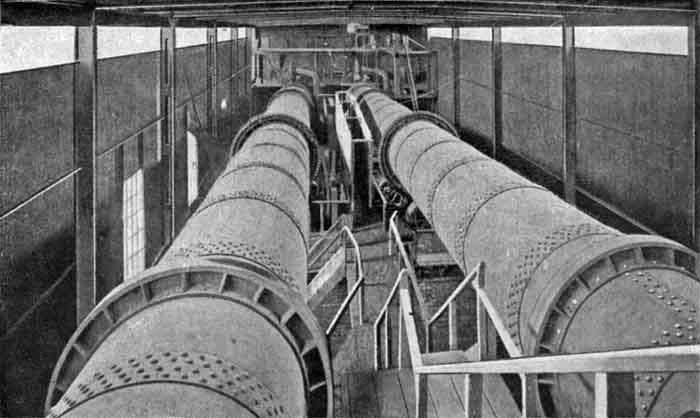

The kilns from the cold end. Note tyres attached directly to the shell.

The kilns from the cold end. Note tyres attached directly to the shell.

View of the physical testing laboratory, with three belt-driven Bohme hammers and a Michaelis tensile strength machine as used by the German Standard. Rows of daily cement samples are on the wall shelves.

View of the physical testing laboratory, with three belt-driven Bohme hammers and a Michaelis tensile strength machine as used by the German Standard. Rows of daily cement samples are on the wall shelves.

The works had been designed for an output of 30,000 tons per annum, but in the first year it produced only 18,000 tons and thereafter about 24,000 tons. The failure to achieve the estimated output was due to lack of knowledge of rotary kilns on the part of most of those concerned. This type of kiln was not new to England, but we had not access to English works and the Board had to rely on information from other countries. There was in those days little inclination among manufacturers of building materials to exchange information. Our Board sternly discouraged visits by outsiders to Beddington, but a Board minute of 18th October 1905, tells us that "a letter was written to Mr Percy Stewart agreeing to his looking over the Cement Works, after the usual agreements had been signed" (Note 9). Sir Percy Stewart later became President of both the Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd and the British Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd.

The chalk for the cement works had to be taken from Coulsdon, and the demand kept the chalk quarry busy for many years. In the first seven months after September 1905, for example, 9,000 tons of cement were made, and for this over 13,000 tons of chalk had to be sent by rail from Coulsdon.

The rest of the story of Beddington Works is soon told. In some years the works made a profit, but there was usually a loss. As time went on it became clear to the Directors that they would do wisely to become cement merchants again instead of manufacturers. Late in 1911 conversations were started with the Directors of the British Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd, and arrangements for the sale to that company, were completed in February 1912. The transfer was effected in June of the same year.

The idea of our adventure into cement making was not ill-conceived, nor were the works an unmitigated failure. It is probable that Mr Joe allowed himself to be over-influenced by his enthusiasm for a long-cherished idea, but there was much to justify his hopes of success. The decision to build was made at a time when foreign cement was coming into England in impressive quantities. At the 1905 Annual General Meeting Mr Joe said:

Many people wonder whether we shall be able to dispose of this cement and keep the works going. Well, I think if I give you a few figures of the amount of cement imported into the United Kingdom you will consider there is room for the output of our works. The total imports are: For the year 1902, 240,893 tons; for 1903, 261,077 tons; and for the year 1904, 272,961 tons. Into London alone, right into the heart of the cement industry, the imports were: in 1902, 14,023 tons; in 1903, 18,026 tons; and in 1904, 27,905 tons. By these figures you will see there is a steady increase, and that the imports to London alone have almost doubled in three years. The prices of cement, I believe, are lower than they have ever been; so, if we can make it pay now we ought to be very much better off when trade has improved, and as we have adopted the most up-to-date machinery now in use by our foreign competitors, we have every confidence in being able successfully to compete with them.

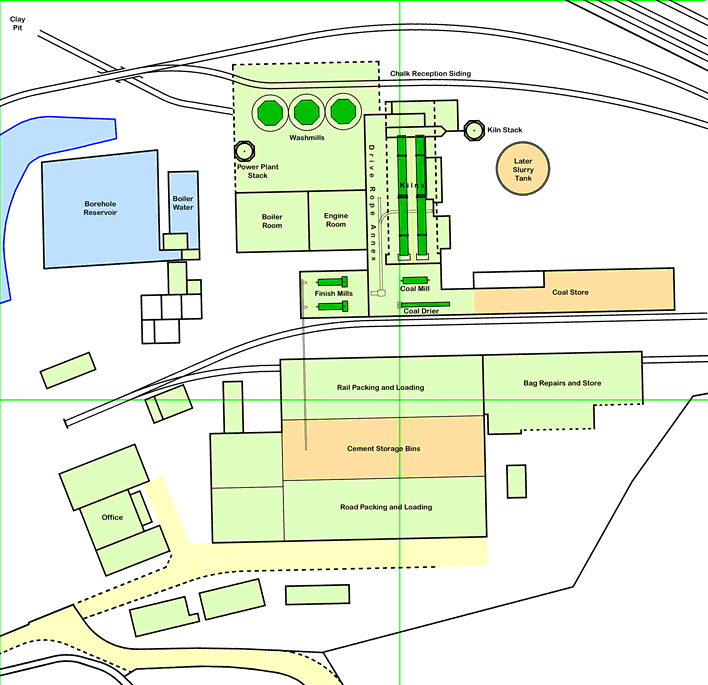

My best information on the plant layout. . View HD image in a new window. A definitive plan of the plant is held in the inaccessible Blue Circle archive. The layout is similar to that of Southam which was also steam driven.

My best information on the plant layout. . View HD image in a new window. A definitive plan of the plant is held in the inaccessible Blue Circle archive. The layout is similar to that of Southam which was also steam driven.

This forecast was over optimistic. Soon after we went into production the building trade ran into a period of depression from which it had not fully recovered when war broke out In 1914. Cement prices remained low in the London area, partly, it must be agreed, because of the existence of Beddington Works.

The Board minutes and correspondence on the cement works are voluminous, and reading them through today, and recalling all that has happened since 1912, we are left with no doubt as to the wisdom of the Board's decision to sell out. By 1910 cement was occupying far too much of the Board's time, particularly Mr Joe's.

It may have been imprudent—it was certainly courageous—to try to enter the cement-making industry, but whatever view we may take there can be nothing but commendation for all those, on both sides, who arranged the sale. The negotiations were friendly from first to last, and the agreement between the British Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd and Hall and Co., Croydon Ltd, effectually restored any goodwill that may have been lost through our building the works. Over the years the goodwill between the Company and the cement makers has grown, and is greater today than at any time in the past.

We continued to supply the chalk for Beddington Works until 1928, when for economic reasons the manufacture of Portland cement ceased there. Before the plant finally closed down, the experimental work that led up to the production of "Snowcrete" white cement was done with Coulsdon chalk (Note 10).