Today a vibrant cement industry is a marker of a developing nation’s dynamism, and world production is dominated by China and India. Meanwhile, the transition from a “cheap-energy” economy to today’s high energy costs and concerns about CO2 emissions have caused a massive decline in the industry in the USA, Western Europe, Japan and Russia. The industry first arose in England in the middle of the nineteenth century, and the progress of cement manufacturing technology in Britain and Ireland exemplifies the factors that encouraged or suppressed innovation.

The purpose of this site is to describe the historical geography of the Portland cement industry in Britain and Ireland, from 1895.

Its historical aspect addresses the progress of innovation, particularly in the field of pyroprocessing that is unique to the industry. Its geographical aspect stresses the way in which the industry’s development is controlled by its geographically-variable natural raw materials: it also addresses the topic in terms of industrial archaeology.

The website is educational and entirely non-commercial, and contains no advertising. No statement should be interpreted as an endorsement of any organisation, company or individual.

How History is lost

A while back, I contacted an old colleague, in order to get detailed information about some cement plants that he had known well. "It's a pity you didn't contact me a few weeks ago", he said. "I've been having a de-clutter, and threw lots of old files and notebooks out." In a contracting industry, old cement plants are closing down all the time. Not unnaturally, those who had been the guardians of the plant's history, lovingly conserving old photographs, ancient plans and ledgers, now find themselves made redundant. They come in to work on their last day, and say "You know what? - I don't care any more! Let's take it all up the quarry, throw some diesel over it, and strike a match."

In my career, I have seen this more times than I care to recall. Don't imagine that such acts of destruction are about "preserving commercial confidentiality" - the details of how a steam engine was coupled to a row of flat-stone mills has nothing at all to do with a modern business. Even twenty-year-old material has mostly ceased to be of any commercial sensitivity. It has a lot more to do with the "Attila the Hun" syndrome: "If I can't have it, no-one's going to have it!"

Sometimes historical material is preserved, but it is placed in the hands of a proprietorial individual or institution who jealously hide it from public view. This, of course, is no more useful than the quarry bonfire. I'm fairly proprietorial myself: I have a huge library of cement industry historical material, and it's MINE! But before I myself decide to "de-clutter", I am trying to make as much as possible available to everybody. I was prompted to draw together all the information I had by this and by a dissatisfaction with the accuracy and technical validity of the existing historical sources. In formalising my own data, I filled gaps and extended its scope by what was, I hoped, a relatively disciplined programme of historical research.

The hope was that the project could be used as a clearing house for historical information on the industry, using the convenient connectivity of a website rather than the restricted circulation of a printed book. Since "nature abhors a vacuum", it was expected that the obvious lacunae in detail would be rapidly filled by public contribution. However, during the period 2008-2026 the content has been refined mainly by gradual acquisition and refinement of information already in circulation. A huge amount of information remains in private hands and there is every indication that it will stay there until it falls victim to time. The current project will continue until the rate of acquisition of new data is insufficient to justify the expense of maintaining the website.

Scope of the Project

The project aims to describe all sites making Portland cement clinker in the period beginning 1895. Outside its scope (although they may be touched upon) are:

- Sites making "pre-Portland" cements such as Roman Cement and various forms of lime

- Sites making other minor sorts of cement, such as calcium aluminates, sulfoaluminates, super-sulfated cements, oxychlorides, "geopolymers" and so on

- Grinding plants making Portland cement using clinker sourced elsewhere.

Criticism might be aimed at the accounts (particularly of individual plants) given here because where hard information is lacking (or at any rate, I have failed to find it), I have given accounts which are to some extent conjectural. Historical discipline would require that I should simply say "not known" under these circumstances. However, the objective of the project is to give a quantitative account of the entire industry. At the heart of the project is a set of databases, invisible to the website (and to everybody else - so don't ask to see it) that completely describe the period of study, and from which can be derived general statements about progress and innovation. These databases, in order to be quantitative, have to have non-zero entries for every entity in the industry believed to be active. This requires that for each plant and each kiln, a "narrative" has to be established. This may involve over-confident interpolation and extrapolation from isolated snippets of data, or even more wild surmises (but hopefully based on informed guesswork) where data is entirely lacking. Where the informed reader encounters glaring (or tiny) errors in these accounts, I can only apologise and urge them to contact me and suggest corrections, which I will be delighted to receive and incorporate.

Why start in 1895? The starting date of 1895 is chosen because the successful use of rotary kilns in Britain started shortly after that date, so the development of that technology is completely covered. Because “Portland cement as we know it” dates from the 1840s, an earlier start date is desirable, but reliable records from the pre-rotary period are extremely patchy and constitutionally inaccurate (by which I mean that they routinely told lies), and the objective of this work is to list all operations in order to produce a quantitative account.

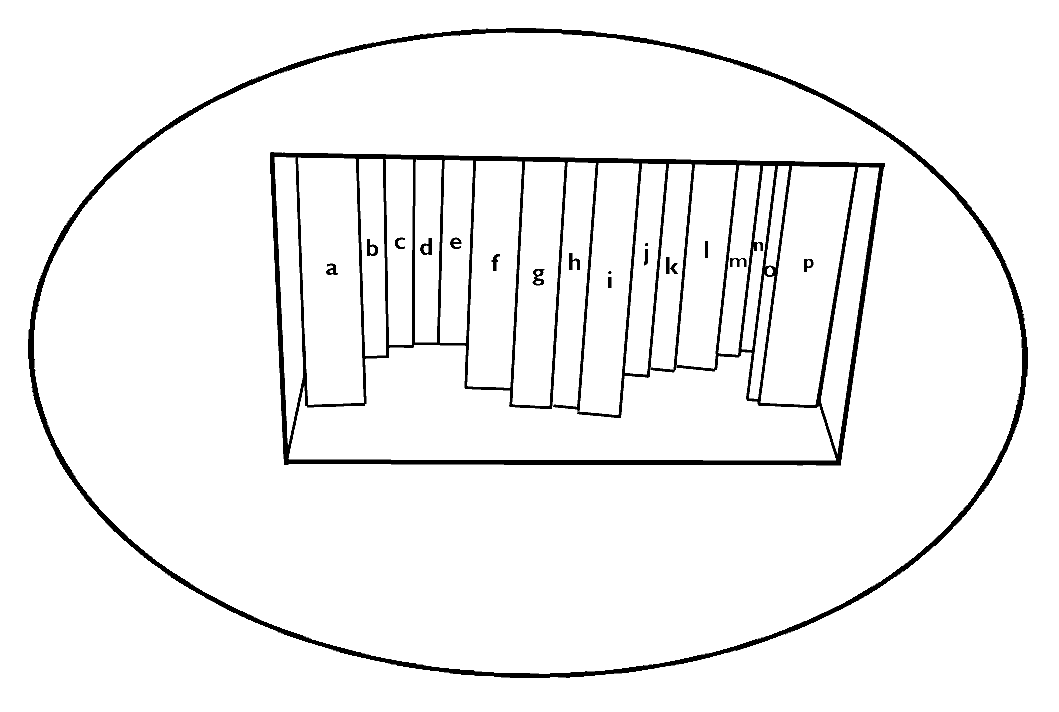

There are now (2026) only fourteen operational cement plants – with sixteen operating kilns – in Britain and Ireland. This site discusses 180 plants that have operated since 1895 and attempts to describe their 340 (or so) rotary kilns while at least mentioning over a thousand static kilns. The resulting body of information makes it possible to derive a reasonably accurate account of the rate and nature of technical change throughout the period.

Privacy and Confidentiality

The information presented here is sourced from the public domain, published material, and from the expert application of personal knowledge and experience. Great care has been taken to ensure that commercially sensitive information is not given. In particular, data concerning the output of plants is presented only in terms of typical capacity, readily available in the public domain, and "actual" production is not stated, except in very general historic terms in order to compare the relative importance of plants. Plants currently in operation are described only in outline in the public version of the website.

This website contains pages specific to the history and geography of the British and Irish cement industries. It also contains pages conveying more general background information about cement and its manufacture. The latter are intended to provide a reliable aid to understanding for historians, geographers and industrial archaeologists. They are not intended to function as a Cement Technology course, and should not be used as such.

In the following statements, "this website" means "www.cementkilns.co.uk" and its associated files. "The user" means any individual, organisation (including providers of search engines), robots, crawlers, spiders and any other entity whatsoever that connects to this website through the Internet.

Copyright Status © Dylan Moore 2010

The original content (text and/or graphics) of each and every page in this website is protected by English Copyright law as extended internationally by the Berne Convention whether or not it contains a statement to that effect and may not be reproduced or adapted without permission except where reproduction falls within the definitions of Fair Dealing listed in the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 and its subsequent amendments.

Care is taken to ensure that the copyright status of images is correctly assigned. Where no statement is made, it is believed that copyright of the original image has expired. However it is the responsibility of the user to establish the status of any image downloaded.

This website is non-commercial, sells nothing, runs no advertisements, has no interactions with users, and neither gathers nor stores any information on individuals.

Disclaimers

This work consists of a website containing a number of pages and the following applies to each and every page. This work is a treatise on history and is not intended to be used for any purpose other than historical or geographical interpretation. The information in the website is provided on the understanding that the website is not engaged in rendering advice and is not to be relied upon when making any related decision. The information contained in the website is provided on an "as is" basis with no warranties expressed or otherwise implied relating to the accuracy, fitness for purpose, compatibility or security of any components of the website. For the convenience of the user, the website contains hyperlinks to websites operated by third parties. Such links are supplied on the understanding that no responsibility is accepted regarding their content, and no endorsement of views, statements or information in third party sites is implied.

Recent Developments

February 2025: Although readership in general continues to fall at 10-15% per annum, my page on the Anhydrite Process, of which I am quite proud, has achieved a high readership, as have the pages on the individual anhydrite plants. Although I despise the proposition that "all history is biography", I find that some biographical detail occurs at multiple points in the website. For instance, there are potted biographies of A C Davis at several places, all slightly different. It is preferable to refer to a common resource for biographical detail on individuals who are often referenced, and I have started writing these, beginning with articles on Henry Osborne O'Hagan and Arthur Charles Davis, and a biographical index

Prior to March 2023, the last cement plant I added to the list was Hartlepools in March 2022. That was a tiny, early plant, that ran for a very short time, and had been easy to miss. However I then found another plant, with a rotary kiln, that ran for 20 years or more between the wars. It is Droylsden. You might well ask - how can a substantial cement plant be completely lost from history for the best part of a century? Read and weep.

Various other long-term projects include raw material databases, accounts of the British Portland Cement Research Association (see index and history), the history of low-heat cement at Rhoose, embellishments of various plant pages for which new information is available and analysis of the recently-acquired Layton archive of early APCM material.

Just recently (Sept-Oct 2025) I have been concentrating on re-organising information on the recently-demolished Bevans, which now allows a more cogent description. Maps, photography from 1925-1928, aerial photography, the Layton archive and APCM minutes have coalesced into a reasonably precise description and timeline. Acquisition of other sources are subject to negotiation. For what I have, I owe a great deal to Chris Down.

December 2025: I did a re-write of Ditton, having found another early rotary kiln. I also transcribed Craske's description of the Medway industry in 1898, and provided some commentary on a Parliamentary debate on dust nuisance in 1948. This prompted me to re-visit some of the descriptions of the earlier Medway plants.

Future Strategy

A recent analysis of traffic showing only a few minutes engagement with plant pages one Friday prompted me to review recent progress. Although pages containing background information are frequently accessed, the plant history pages are obviously the main reason for the existence of the website.

User engagement: plant history pages

User engagement: plant history pages

After a "COVID-boost", the trend has been a rapid decline, and without another pandemic, the situation is unsustainable. I have therefore started to wind the public site down. The website will still, of course, "stand in the night, after the locks and chains".

About me

On the raw material preparation page, there's a photo of an xrf bead that I took back in 2002, as part of a training programme. I recently noticed that some of my bookshelves can be seen reflected in the bead. In comparison with the exasperating difficulties involved in researching 100-year-old cement plants, it was quite easy to identify many of the books.

- Ekwall, Dictionary of English Placenames

- Myres, The English Settlements

- Bede, History of the English Church and People

- Brooke, The Saxon and Norman Kings

- Brooke, From Alfred to Henry III

- Hallam, Rural England, 1066-1348

- Bolton, The Medieval English Economy

- Goldberg, Women in Medieval English Society

- Gimpel, The Medieval Machine

- Ziegler, The Black Death

- Keene, English Society in the Later Middle Ages

- Defoe, A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain

- Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year

- Cippola, Economic History of World Population

- Houston, The Population History of Britain and Ireland 1500-1750

- Wrigley & Schofield, The Population History of England, 1541-1871

I didn't select these, honest! It's just a literal "snapshot" of about 1% of my library. Anyway, so much for books. I work on the following assumptions:

- The driving force of history is economics.

- Economics is the mass action of the entire population.

- Individuals, great or small, have zero effect on history.

In view of the fact that I have recently (2025) started to include biographical information, I should mention that this is not to suggest that those individuals I mention had any effect on history - only that they, like myself and a million others, were sucked into its maelstrom.

Everything else relevant about me used to be found in my LinkedIn profile, but since LinkedIn made its political stance clear by systematically directing me to the outpourings of Fascist politicians and bar-stool Nazis, I closed my account in January 2026, so I suppose I will have to add a few autobiographical notes.

Up to 1973. When in a thousand years time I'm dug up again, they'll find in my teeth the strontium isotopes characteristic of the Chilterns. I was born and bred in Luton, Bedfordshire, and after several million kilometres of travel, I still regard those chalk downlands as home. I became a chemist. I came away from University with no PhD and clinical depression. My essay About Chemistry might be of interest. In it, I describe the cement industry as a chemistry-free zone, but in 1973, I ended up there. I have never been able to imagine anyone actually choosing to join the cement industry - it's just somewhere you end up.

1973-1976. I joined the British cement industry in 1973, which was, coincidentally, its peak production year, in which just over 20 million tonnes of cement were made. I played only a very minor role in its subsequent massive decline. I began by taking an hourly-paid job as relief slurry tester at Sundon. I was taught cement process technology by Len Hillsdon. I was identified as being in too lowly a role by the Northern Area Chief Chemist, John Davies, and was made Senior Chemist for the plant - deputising for the Technical Manager. They sent me on all sorts of courses, of which probably the most useful was "Train the Trainer", but I also did a slurry testers' course, which allowed me to get to understand the wide range of different manufacturing environments existing around the country. Then there was the Cement Technology course, which was mainly a not-too-persuasive advertisement for the Northern Area graduate recruitment process. There were a lot of very angry delegates. In 1976, I got my first taste of the essential nature of the post-1973 cement industry, with the closure of Sundon. This taught me a valuable lesson: in an industry in inexorable decline, most careers will end in redundancy, so it is important to conduct one's career in order to optimise one's position when it finally ends. In December 1976 I was made redundant for the first time.

1977-1979. I was give the role of Technical Assistant II at Humber, taking the place previously occupied by Ron Mayman. I was able to read (but unfortunately failed to steal) his diaries, dating back to the late 1920s. The change from Sundon was an enormous culture shock, moving from a family-like environment full of hard-working, helpful people to a bloated over-manned organisation sunk in moral turpitude - all this is mentioned in my Chemistry essay. The inevitable long-overdue closure of the plant was fast approaching, and I got out before the end.

1979-1991. Because of my reading matter at the time, I characterised the move to Shoreham in February 1979 as going from Gormenghast to Cold Comfort Farm - Humber did indeed have flaking cherubs outside the office building. I took the role of Deputy Technical Manager. I did all the things such people are expected to do. As at the other plants, I could mention a list of milestone achievements, but in retrospect, I can't be bothered. None of it today would be regarded as marketable. The plant was a pilot for the conversion of Northfleet to the doomed semi-wet process. The plant closed in 1991 and I was redundant for the second time.

1991-1993. I became Scientist(!) at Blue Circle's Research Department, really just treading water until something useful came up. My background - a graduate, but not hired as such, with experience of the process from the bottom up - became a peculiar asset in the rarified atmosphere of Greenhithe. I started visiting all the Blue Circle plants doing technical survey work, and was sent to Lichtenburg, South Africa and Sirohi, India on XRF-related work. It was on these many trips that I came to realise that my expertise in my various specialisms - raw material preparation, clinker chemistry and x-ray methods - was superior to any in the company, and probably in the world. A particularly good facility at Greenhithe was the Library, including a large back-store, containing mountains of historical information that I absorbed during my short stay there, and on many subsequent visits. Another trip that was organised for me was to the USA, and this led to a more-or-less permanent placement.

1993 to 2002. In 1991, at Atlanta GA, some cheap, not-too-pure kaolin had been obtained, and evidently a brainstorming session had been organised to try to find something to do with it. The plant was in recession at the time, and it was decided to use the spare capacity to make off-white cement and, more speculatively, expansive cement. As was de rigueur at the time, Greenhithe was asked to provide expertise on the latter - and they duly complied, despite a complete lack of knowledge of the subject. Looking back, I imagine they thought the project would naturally fail in due course, and so sent the lowliest of their staff - me - on a brief trip to supervise the burn. It involved making a sulfoaluminate clinker containing ye'elimite. The content of ye'elimite, anhydrite, free lime and silicate phases in the clinker would be assessed by x-ray diffraction - an ancient third-hand XRD instrument had been obtained. I had no experience of XRD since leaving university. Greenhithe provided me with two home-made XRD calibration standards, both of which had in fact been overburned to the point where they contained no ye'elimite. To the delight of some Americans, and the consternation of some Brits, I made about two thousand tonnes of reasonably good sulfoaluminate clinker on Atlanta Kiln 1, by ignoring (with well-deserved contempt) all instructions, looking in the kiln, and trusting my instincts. On the strength of this, I was invited back to Atlanta on a permanent basis in 1993, as Technical Manager for production of these special cements.

As at many US cement plants, Atlanta had been extraordinarily backward in its chemical control, still using classical gravimetric analysis, even on shift. On the plus side, this gave me access to a laboratory set up to do actual chemistry. I used selective-dissolution techniques to determine the mineralogy of the clinkers. I made my own XRD standards, such as pure samples of ye'elimite, ternesite, ellestadite and tricalcium aluminate. A funny story: I took some of my synthetic ye'elimite back to Greenhithe to get it checked for purity. I was disappointed to be given the XRD scan with several peaks marked as "impurities". It happens that Hal Taylor was paying a flying visit to Greenhithe, so I grabbed him, asking if he knew anything about XRD. A bit, he said. I asked if he could identify the impurity peaks in my scan. After a few minutes of calculator work he said "No - they're all ye'elimite - peaks that have not been reported in the literature". It would appear that a sample this pure had never been obtained before. I made it by a special technique. When I told the Greenhithe people about this they said "can we have some?"

We went on to make a quarter of a million tonnes of expansive cement at Atlanta. It was gradually abandoned as the market picked up and the production capacity was needed for ordinary cement. I moved my desk to Blue Circle North America head office at Marietta GA, acting as North American QC manager. In this role I got involved in the activities of the PCA (now American Cement Association) and the American Portland Cement Alliance. My activities at the latter produced cost savings that handsomely repaid the entire cost of my nine years US salary and expenses, although it would appear that my boss had no knowledge of my involvement. I also represented the company at ASTM, becoming chair of the subcommittee on Chemical Analysis for a while, and I remain an occasionally-active member.

2002 to date. With the takeover of Blue Circle by Lafarge, I was made redundant for the third and last time. I was offered jobs by Lafarge and several other cement firms, but it was now time to cash in on the very generous severance package that Blue Circle provided; taking work abroad would have made a huge dent in it, and prospective employers offered much less lucrative severance deals. I returned to the UK in due course, and have since been semi-retired, living on investments, doing occasional consultancy work if the job appealed to me. This has been mainly in the field of sulfoaluminate cements, and mainly for governments. I have not lost the taste, gained in the USA, for good food, first-class travel and five-star accommodation.

Acknowledgements

My warmest thanks go to many individuals from whom I have received much help and encouragement in the preparation of this work, and primarily my greatest mentor, the late Len Hillsdon, who began my interest in industry history. Others include David Baird, Alan Betteney, Richard Bull, Tom Burnham, David Challis, Aarlen Collier, Graham Deacon, Peter del Strother, Alan Dinnis, Chris Down, John Frearson, Murray Hislop, Michael Kapphahn, Phil Kerton, Paul Meara, Graeme Moir, Rainer Nobis, Mark Peters, Jim Preston, John Scott, Edwin Trout, Richard Turner, Ruth Waller, Richard Walsh, and many more too numerous to mention.

My thanks are also due to the staff of the many libraries and archives that I have consulted, listed in Sources.

Although much of the information on these pages is indisputably correct, some descriptions of plants have been tentative due to the paucity of evidence available. I welcome all suggestions for corrections: please contact me with these.