There is very little evidence about the history and technical details of the Wareham plant of the Dorset Portland Cement Company Ltd. Here are two newspaper articles that describe the plant. It is curious that, despite a 25 year interval between them, the accounts are uncannily similar, and give an impression of the self-satisfied stasis that characterised the British industry in its decline.

The first is from the Dorset County Chronicle & Somersetshire Gazette, 21/7/1881, p 7, when the plant had been making cement for six years.

CEMENT MAKING. — A few mornings since I satisfied my curiosity by calling at the cement works at Ridge. They are built upon land, which was apportioned with other allotments to the “squatters” when the large tract of common land, which is seen on the left of the road leading to Corfe Castle, was enclosed some years since. I was not long in making the acquaintance of Mr T. P. Powell, the proprietor, who, after enquiring if I had seen works of that kind before, and my replying in the negative, informed me that the heaps of “marl” which I saw lying in the yard was the principal ingredient used in making cement. A number of carts were at work bringing this “marl” from the quarries belonging to these works, on the Purbeck hills near Creech (Note 1). It being a fine day I could clearly see the tramway down which this “marl” is lowered by means of a double action drum, saving many miles of cartage by way of Corfe Castle. Turning our steps towards the extensive buildings, we came upon the manager, Mr Dibben, giving instructions as to the working of the kilns. He accompanied us over the works and pointed out several important labour saving improvements recently introduced. The “marl” is passed through a mortar pan and worked into a plastic state, then it is mixed with a dry ground “marl” and put through a pug mill, coming out in the shape of bricks, which are wheeled into the yard and stacked on hacks for drying (Note 2). There are four kilns used for burning these bricks, which are laid alternatively with coke, taking about thirty hours in the process, during which the bricks become reduced about one-third in weight and rendered into clinkers. These are passed through a powerful Blake's crusher and reduced to about the size of walnuts. This is raised to the hopper box above the mill stones by means of an elevator. After passing the stones, the cement (which, I think, it must be considered by this time) is conveyed by a long horizontal screw to an adjoining room, from which elevators raise it to the sieve on the top floor. Just one minute in this room, for the dust is almost blinding and we retire below to discuss the further progress of the cement. I am told that the sieve, through which all the cement passes, has 1600 meshes to the square inch. That which does not come up to the crucial test passes below to a small pair of stones, and is then carried up again to the sieve. After undergoing this process it is run down into bins to the floor below. Here there is a very large stack in bulk, as well as on the ground floor, and it is from this that the men are weighing it in bags and putting it into casks ready to be sent away. The machinery is worked by a powerful horizontal condensing engine, the flywheel of which weighs four tons and measures twelve feet in diameter. This and the double-flue Cornish boiler was supplied by Messrs Lewin, of Poole. The qualities of this cement were afterwards tested with a Michele's machine - briquettes were placed in it. The first (two months old) stood the test of 1400 lb to the 1½ in by 1½ in section. One at one month old broke at 1000 lb. and the third (only 6 days old) stood the test of 1000 lb and did not break (Note 3). All these were immersed in water when only a day old. This, I believe, is equal to any cement that is made, it being considerably beyond the Government requirement, and is spoken well of in a number of testimonials. It is not an unusual thing for cement to be spoilt in its manipulation by the workman either mixing too much at a time and allowing it to become spent before he can use it, or by neglecting to mix the same proportion of water and cement throughout the work. Any deviation from this latter rule ruins the cement and will produce different shades of colour when dry. It might be stated that it is indispensible for good work, that clean washed gravel or sand should always be used, as any loamy or dirty substance would spoil the vitality. The correct gauging should be ascertained and no alteration made therefrom on the same job.

In 1906, we have a strikingly similar newspaper article (Western Gazette, 9/2/1906, p 10), describing a Wareham plant that clearly has hardly changed at all in the intervening 25 years, and displayed - for the time - an extraordinarily primitive technology.

AN OLD DORSET INDUSTRY

These are the days when the important subject of our national fiscal policy is being hotly debated on all sides, but, notwithstanding the differences of opinion which the consideration of this fateful question has disclosed among us, there is still, happily, one point upon which we are all of us in general agreement - namely, that where the native product is at least of equal merit with the foreign, it is eminently desirable to support home industries, and that where, as in certain cases, the former can be shown to be a far superior and more reliable article, the unwisdom of continuing to purchase from the foreigner is still more manifest (Note 4).

To Dorsetshire men with their ever-present local patriotism, this argument cannot fail to appeal with particular force, and as a Dorsetshire man myself it was therefore with great satisfaction that I accepted an invitation from the Dorset Cement Company to make a personal inspection of their works at Ridge, near Wareham, and form for myself some idea of the progress and perfection to which the art of cement-making has nowadays attained. Taking an early opportunity of availing myself of the offer, I arrived at Wareham by the 9.24 train last Tuesday, and after making a rapid survey of this historical old Dorset town, I drove away through charming country in the direction of the works. I could not help, on my approach, contrasting the conditions of labour carried on in the delightful country that surrounded me on all sides, and those that obtain in the dingy hives of industry, which are so characteristic of our Northern and Midland counties. Here in this healthful moorland air, I said to myself, must surely be power to the arm, vigour to the brain, of both master and workman, and, on alighting, it was no surprise to me to note the keen and intelligent look, the alert step, with which all concerned went about their business.

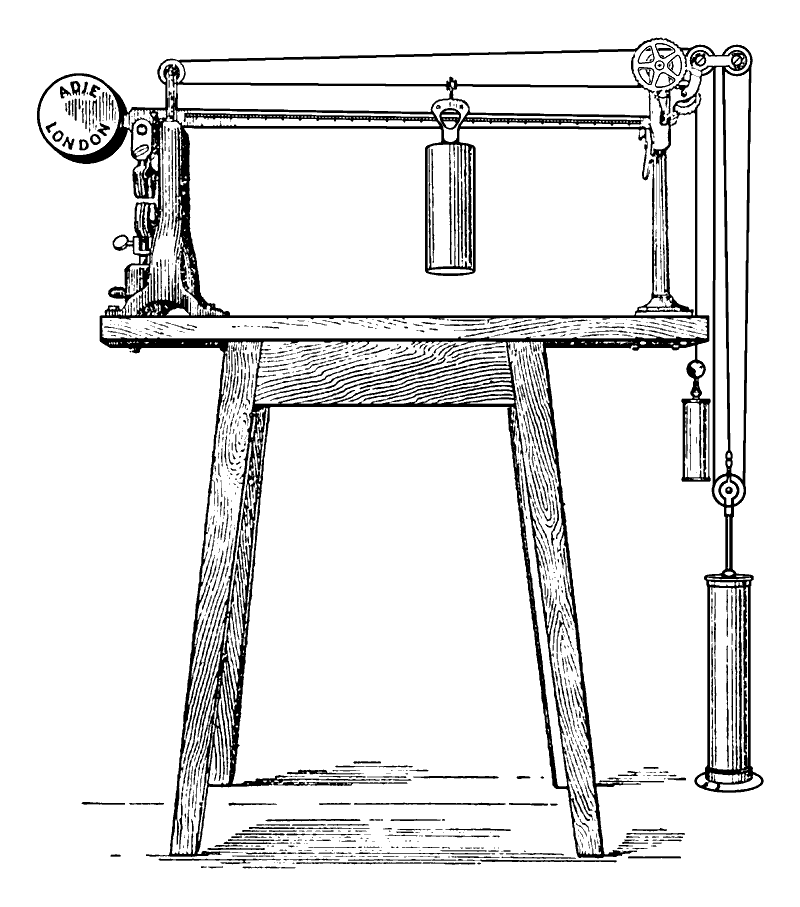

I was received at the office by Mr J. N. Smith, one of the partners in the firm, and was first taken to the testing-room, where an interesting ten minutes was spent in observing the enormous strains to which briquettes of cement are here subjected - in some cases a thousand pounds to the square inch being the breaking-point recorded by the testing-machine (Adie's Patent) (Note 5). I was also enabled to examine the very complete equipment provided by this firm for the analysis both of the raw material of cement and the manufactured article. No-one who has not actually been admitted into the interior of a modern cement-maker's laboratory can form any idea of the scientific exactitude, which, in order to prevent all risk of the occurrence of catastrophe to building, sea-wall and reservoir, must prevail in these investigations (Note 6). Mr Smith informed me, with not unnatural pride, that not the smallest consignment of cement is allowed to leave the works without being first subjected to the most rigorous and up-to-date tests. Next, it was suggested that as I was anxious to witness the entire process of cement-making from beginning to end, we should first drive to the Company's quarries, which lie among the famous Purbeck Hills.

On the way Mr Smith informed me that the firm is in possession of mining rights over many acres of marliferous land, from which to draw a never-failing supply of the necessary raw material of the cement. On arrival at the quarries my attention was first taken up by the arrangements made for the conveyance of the marl from the pit-mouth down a precipitous incline to the road below by the utilisation of the force of gravitation. Then, still accompanied by my courteous guide, I stepped into the cage, and was lowered down the shaft, so as to obtain a view of the underground workings (Note 7).

After having had explained to me the skilful method of timbering the many corridors, which is here employed, ensuring, as far as man may, the comfort and safety of the workers. I negotiated the return journey, and shortly re-appeared on the surface. Having now seen the marl excavated, we drove pleasantly back to the works to witness the variety of processes through which it must pass before it can attain to the dignity of a cement, on the way overtaking a powerful traction engine with its train of trucks, laden with the produce of the quarries.

To begin with, the marl goes into the maw of a mysterious machine (Note 8), from whence it emerges in a plastic state, and is straightway cut into brick shapes for convenience in handling. These are placed in artificially-heated drying-rooms, where they remain until thoroughly dried. Next I was shown the firm's line of kilns, in which the bricks are subjected to a fierce heat for the best part of a week., at the end of which the bricks are taken out in the form of clinker. Leaving the kilns, Mr Smith then conducted me to the "crusher", as it is called, where the clinker undergoes its first reduction. Subsequently, he explained the method by which, after the material leaves the crusher, it is not again handled until it is filled into sacks ready for carting away. This is accomplished by an ingenious arrangement of automatic carriers from machine to machine, in different parts of the building, until the cement is finally deposited in the numerous capacious bins awaiting it.

The next visit paid was to the well-appointed engine-room, where a powerful horizontal engine, whose fly-wheel weighs, I was told, many tons, was pulsating energetically. Then after a brief inspection of the blacksmith's and carpenter's shops, which the firm maintains on the premises, I had to hurry away, as time was beginning to press, to the various stores, where the Company's large stocks, not only of cement, but also of lime, and agricultural manure lime, the latter manufactured by a secret process, are stored away. This done, I had seen the whole process of cement-making, and was next shown a number of testimonials from eminent firms, all witnessing to the perfect satisfaction which the article I had just seen manufactured gave to customers. I was specially interested to learn from documentary evidence that the Company's cement had passed the stringent tests insisted upon by such bodies as the Admiralty and the Board of Works. After thanking Mr J. N. Smith for his courtesy and attention in explaining to me the many mysteries associated with this interesting industry, I now took my departure, well pleased to find that in these so-called degenerate days, there are at least a few businesses still carried on amongst us in a progressive and enterprising spirit and on strictly scientific lines, and that in my native Dorset there exists a manufactory so capably and energetically managed as the Dorset Cement Works.

J.W.F.